Did you know that turkeys are descendants of dinosaurs? That’s right, the turkey and the Velociraptor share similar skeletal structures.

That’s not even the most interesting fact about turkey anatomy! There are many parts of a wild turkey that are amazing in appearance or function.

Whether you are a hunter, bird watcher, or chef, you are probably interested in turkey anatomy. This brief overview covers the head, the organs, the legs, and wings of this wonderful creature.

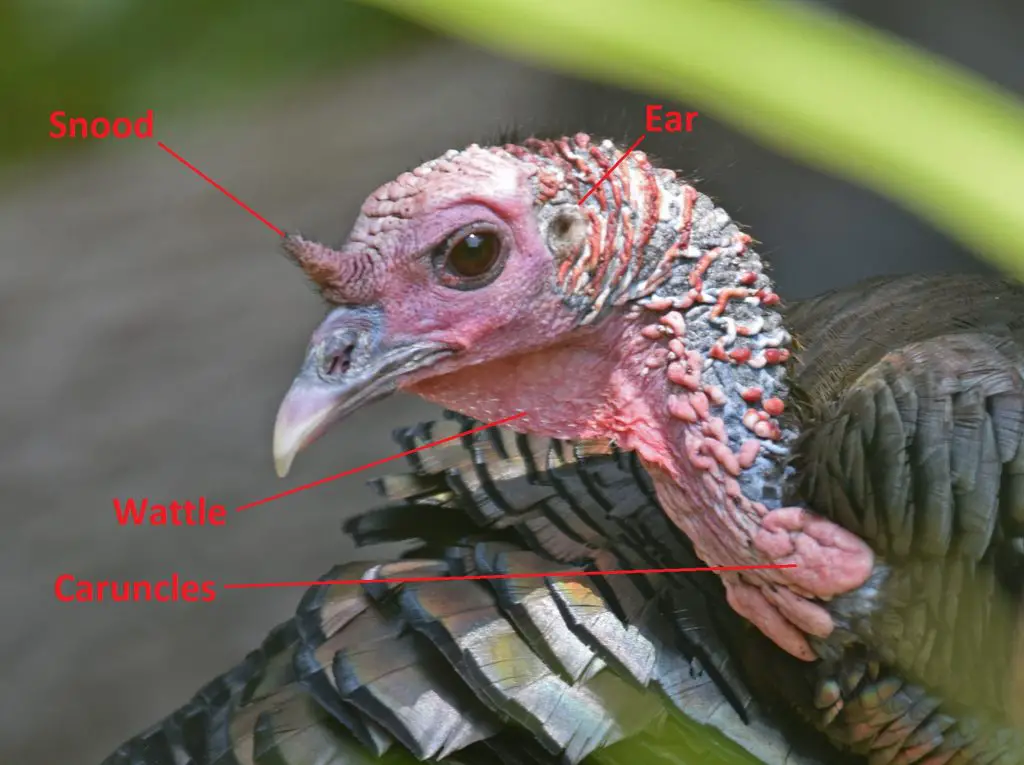

Anatomy of a Turkey Head

The turkey’s head is a facinating thing! The All-American bird’s head can be red, white, or blue at any given time.

But what are all these warts, and lumps, and dongles hanging around? What is their function?

Let’s jump into it as we look at the turkey anatomy of a head.

Snood

The Snood is one of a wild turkey’s most unusual body parts. It is attached to the top of the head.

Both toms and hens have a snood, but it is much longer on a tom. The snood is full of blood and will elongate and shrink according to the tom’s mood.

While we are not 100 percent sure what the snood is for, we know that it aids the tom in attracting a hen for mating during the spring.

Wattle

Like the snood, the wattle can also indicate the turkey’s mood. Hanging under its chin, the wattle can grow, shrink, and change color.

It plays a role in attracting female turkeys for mating. According to the Audubon Society, it is also useful during the summer for releasing excess heat.

Caruncles

While you may have thought turkeys have warts, those big bumps on their neck are technically called caruncles. Caruncles are primarily decorative. Their role is, you guessed it, attracting a mate.

Like the wattles, the caruncles may also help in helping the turkey to keep cool.

Ear

Arguably the turkey’s greatest sense is his hearing (his eyesight would be a close second). Turkeys can hear a soft cluck from a longgggg way away.

The ears appear externally as two small holes further back on the head than the eyeballs. They have specialized feathers to protect the ear opening.

You may see a turkey move his or her head when trying to analyze a sound. Because turkeys don’t have ear lobes, the turkey is using its entire head to funnel the sound into its ear.

Eyes

A turkey can see 270 degrees without moving its head. This is why it is so hard to move when a turkey is around without getting busted. Always make sure they have their head fully behind something before you make any movement.

While turkeys can’t see very well at night, they can see amazingly far with a lot of color. According to Scientific American, turkeys can see up to three times better than 20/20. They also have six different types of cones in their eyes (compared to three single cones in a human eye) allowing them to see in amazing color and even in UVA.

Turkeys have a third eyelid known as a nictitating membrane. This nearly-translucent lid is used to clean and lubricate the eye. Essentially, the turkey does not have to blink with the upper and lower eyelids as we humans do, so they can keep their eyes open and on the lookout for danger.

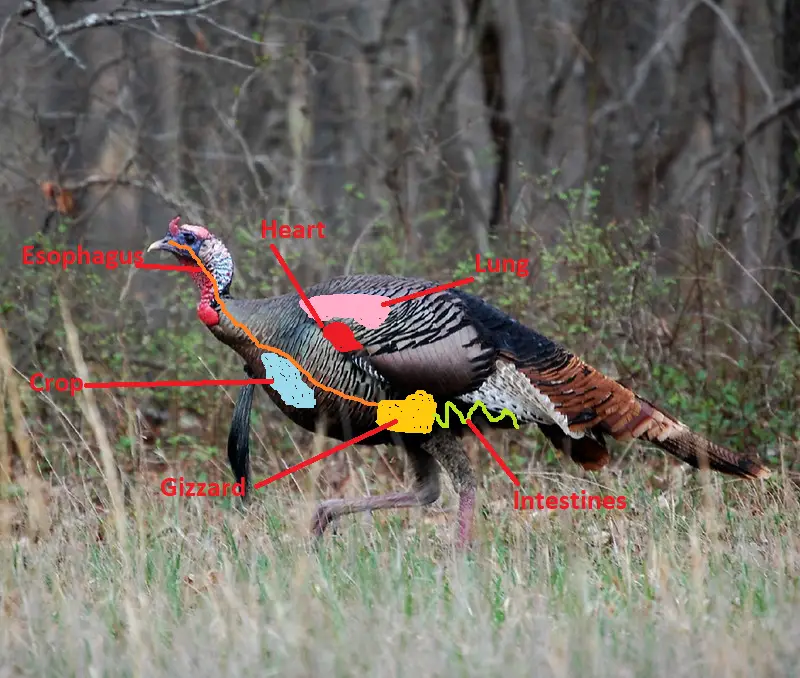

Turkey Anatomy of the Organs

Like humans, turkeys have a four-chambered heart. However, that is one of the only similarities between turkey anatomy and human anatomy. Let’s dig a little deeper into what keeps the turkey going.

Crop

Turkeys eat a wide variety of food. For many years, hunters and researchers have examined the contents inside the turkey’s crop to determine exactly what these guys are eating.

Turkeys use their beaks to pick up food and start it on its digestive journey. From the beak, it goes down the esophagus and into the crop.

The crop sits just in front of the breast of the turkey. It can hold up to a pound of food. Food will usually pass on from the crop within a few hours.

As a hunter, you can utilize the contents of the crop from a harvested turkey to help you in your scouting. Knowing what that turkey was eating lets you know what food sources to target to find more birds.

Gizzard

After leaving the crop, the food continues down the turkey’s esophagus to the gizzard. The gizzard is a muscular organ just above the intestines.

The gizzard is where the turkey’s food is broken down. In fact, the food is literally ground up. Turkeys swallow rocks and sand particles. These hard objects are ground against the food to smash them and allow them to pass.

Eventually, the rocks are ground into sand and passed through the system as well. The turkey must continue to consume grit in order to maintain the digestive system.

After food leaves the gizzard, it is passed into the intestines.

Breast Sponge

If you are cleaning a spring tom and find a layer of fat over the crop, don’t freak out.

Toms develop this layer of fat known as the “breast sponge” or “turkey sponge” during the winter. During the spring, they live off this fat as they become too preoccupied with breeding to consume enough calories.

Hens and younger toms do not generally have a breast sponge.

Heart and Lungs

For archery hunters, knowing where the heart and lungs are is the most important lesson in turkey anatomy.

The vitals on a turkey are small. Basically, the size of a softball. That doesn’t give you much room for error.

If you draw an imaginary line between the points where the wingbones meet the body on both sides, this is the area of the vitals. On a tom turkey facing you, the heart and lungs are going to be aligned with a point just above the beard and just below the base of the neck.

For more information on aiming points on a turkey, read my articles on turkey hunting with a bow and crossbow.

Turkey Anatomy of the Leg

As most hunters know, turkeys can move fast. In fact, they are capable of running 25 miles per hour. Read on for more information about some of the interesting parts of these powerful legs.

Toes

Turkeys have three forward facing toes and one backward facing toe. The backward facing toe does not always touch the ground.

The tom turkey has longer toes than a hen turkey. Turkey tracks longer than four inches are usually male turkeys.

Spurs

The spurs are located on the back of the leg just above the back toe. The spur is made up of keratin, the same protein that produces hair, skin, and nails in a human.

Spurs are most prominent on mature toms. Jakes have short spurs that are generally less than an inch in length. Hens can have spurs, but they are very small and rounded.

Toms use spurs to fight other toms and establish dominance. To learn more about turkey spurs, read my article on the subject here.

Thighs

The thighs of the wild turkey are much maligned. Many hunters have been known to “accidentally” slip the legs of a harvested turkey to their canine companions.

This is a shame as the thighs can actually be very good eating. When braised in a slow cooker or dutch oven, the meat is not as tough as it can be when cooked fast and hot. Shred the meat and toss it in barbeque sauce and it makes a great sandwich!

Wings

Unlike their domestic cousins, the wild turkey is fully capable of flight. In fact, the turkey depends on its wings to get it in an elevated position to roost.

According to birdfact.com, turkeys fly at an average speed of 55 miles per hour. However, their flights are short. Rarely will a turkey fly more than a quarter mile.

For the most part, a turkey will walk or run unless it absolutely has to fly. Those of us who tried to call a gobbler across a ravine know this all too well.

Conclusion

Hopefully, you’ve learned something new about turkey anatomy today! As you can see, there are many intricacies that make the turkey very unique.

Now the next time you harvest a turkey, you’ll know a little bit more about the body as you process the meat. Maybe you’ll even be brave enough to taste a gizzard!